Over the past two years, we've created four courses, accumulating 2,500+ students. Recently, you may have seen many student projects shared in our updates—they're truly impressive, and I've been inspired by many of them. But those who actually delivered products that everyone can use are actually a minority who made it to the finish line.

We haven't had the chance to discuss the other side: based on our observations and interviews, a surprisingly large proportion of students actually stopped somewhere in the middle. They didn't finish and think it was useless, nor did they give up because they couldn't learn—they hit a certain point where their enthusiasm ran out and quietly disappeared.

What frustrates us most is that this attrition often doesn't happen in front of complex algorithms or logic, but at extremely trivial obstacles that have nothing to do with core skills.

Facing this attrition, the traditional educational instinct is to create more content—if you don't understand configuration, we write a document; if you can't deploy, we record a video. But as tutorials pile up and learning paths grow longer, those trivial obstacles remain. So we believe that in the AI era, we might need a more fundamental approach to truly solve this attrition problem.

This article aims to step back from discussing solutions and first systematically examine where people learning AI actually get stuck, then explain how we're trying to eliminate these obstacles at their root using an engineering-oriented approach.

The Attrition Ladder: Four Critical Nodes in Learning AI

The attrition process where student enthusiasm runs out is like a staircase. At each step, some people stop for various reasons, while those who cross over experience a qualitative leap in their abilities.

First Step: Brain Says "I Get It," Hands Say "No, You Don't"

From the very beginning of teaching, we found that many students watch the videos, read the materials, feel like they understand, but never actually apply AI to their own lives or work.

This is a real shame. Learning AI is more like learning to swim or fly a plane. Just as no one can learn to swim by watching videos, you can't learn AI just by reading materials. Knowledge points can be acquired through memorization and understanding, but skills must be developed through physical practice. You have to stumble through real scenarios—especially make mistakes in real scenarios—to truly internalize it as your own ability. There's a huge chasm between the brain thinking it understands and the hands actually being able to use it.

This is why we say this step is the starting point: if a student has never applied AI to a single real task—even a very small one—they haven't truly started learning. Many people stop at this step. They think they're learning, but they're really just watching others learn to create an illusion that they're making an effort.

Second Step: From Toy Projects to Real Applications

Some students cross the first step, complete a few small projects from tutorials, and build some confidence. But when they want to make something truly useful, or want to use it at a slightly larger scale or with some automation, they find a pile of chores ahead: binding credit cards, registering for various accounts, applying for API tokens, configuring development environments. It's all grunt work with no sense of achievement when done, and people give up after a bit of frustration.

The problem with these chores is that they contribute almost nothing to the learning objective, yet consume huge amounts of enthusiasm and time. You were ready to tackle something big, but two hours later you're still wrestling with configuration and haven't written a single line of code. So giving up is human nature.

At the same time, this sense of defeat is fatal. Drive is most fragile and needs the most protection when it's just beginning to sprout, because once it's extinguished, it's hard to rekindle. The result is that students have just built up confidence, finally crossed the first step, started believing they could do something—and then these trivial configuration tasks knock them back down. So this friction is truly hateful and must be addressed seriously from a teaching perspective.

Third Step: From Passive Reception to Forming Your Own Judgment

Some students endure through the first two steps, finally get the API running, start using AI to do things, and accumulate some experience. But then another problem emerges: their firsthand experience can't scale. They have some opinions and insights within their own small domain, but most of the time they're still led around by clickbait headlines. Today this article says Claude is best at coding, tomorrow that one says DeepSeek crushes everyone on cost-effectiveness. Without their own firsthand experience, they can only parrot others.

The essential barrier at this stage is: distilling your own insights from complex information. True learning requires doing a large amount of scalable experiments yourself to accumulate firsthand experience. This isn't as simple as trying a few models—it requires repeatedly comparing and repeatedly hitting pitfalls in real scenarios. Run the same task through three models, record their respective performance; switch back and forth between different prompt strategies to feel their differences. Only this way can you form your own judgment, rather than believing every article you read.

This step is important because it touches on the essence of learning AI: knowing how to call an API is far from truly making a useful AI product. What's crucial is learning how to make trade-offs and judgments. Technology will change, models will iterate—only judgment can be accumulated and transferred. Without firsthand experience, you'll never form your own opinions, forever believing whatever others say. In this state, you can't truly use AI well, because every decision depends on others' (or even bloggers') conclusions.

Fourth Step: From Running Locally to Deployment and Delivery

The final step: the code runs locally, but it's stuck at localhost:8000—no one but yourself can use it, just self-entertainment. When you tell others AI is amazing, that "you" are amazing, they have no concrete sense of it.

Deployment itself isn't hard, but for beginners, it means yet another pile of new concepts—servers, domain names, Docker, CI/CD. Each one can become a blocker, each one requires additional learning cost. Many students stop at this step: they made something, but only they can use it, they can't share it with others.

This step is a critical turning point, not just technically. The moment a project can be accessed by others, it transforms from homework into a work. It can be shared with friends, put on a resume, or even used by real users. This identity shift completely changes how students view learning AI—from "I'm completing exercises" to "I'm creating value." We've observed that many students' learning enthusiasm truly ignites the first time they share their work. Before that, it's passive learning; after that, it becomes active exploration.

How to Solve the Problem at Its Root

If we carefully observe the four steps described above, we find they're essentially friction problems. The traditional solution to such problems is to give you more tutorials—teaching you how to register for APIs, how to configure environments, how to buy servers. Every time you hit a pitfall, write a tutorial to teach it. The result is more and more tutorials, longer and longer learning paths, but the same amount of work to do, and friction hasn't really decreased.

This is also why tutorials are everywhere in the AI era. Honestly, this isn't the fault of tutorial authors or the community, because traditional teaching is more like Content Creation, or being a content creator. When people think of teaching, they can only think of writing textbooks, recording videos, giving lectures. Building a platform specifically for teaching is, if not impossible, at least not the first thing that comes to mind. It's a thankless task, and the skill set doesn't match.

But this is a mental model we want to challenge: if registration, card binding, and configuration contribute nearly zero to learning objectives, why let them exist on the learning path? Instead of writing documents teaching you how to bind a credit card, why not make the credit card binding step disappear entirely? In the AI era, we at least have this option—to actually Build a platform that eliminates this friction in one go, letting students seamlessly cross these steps and spend all their time on the most important skill practice.

This is the starting point for why we built AI Builder Space.

What AI Builder Space Does

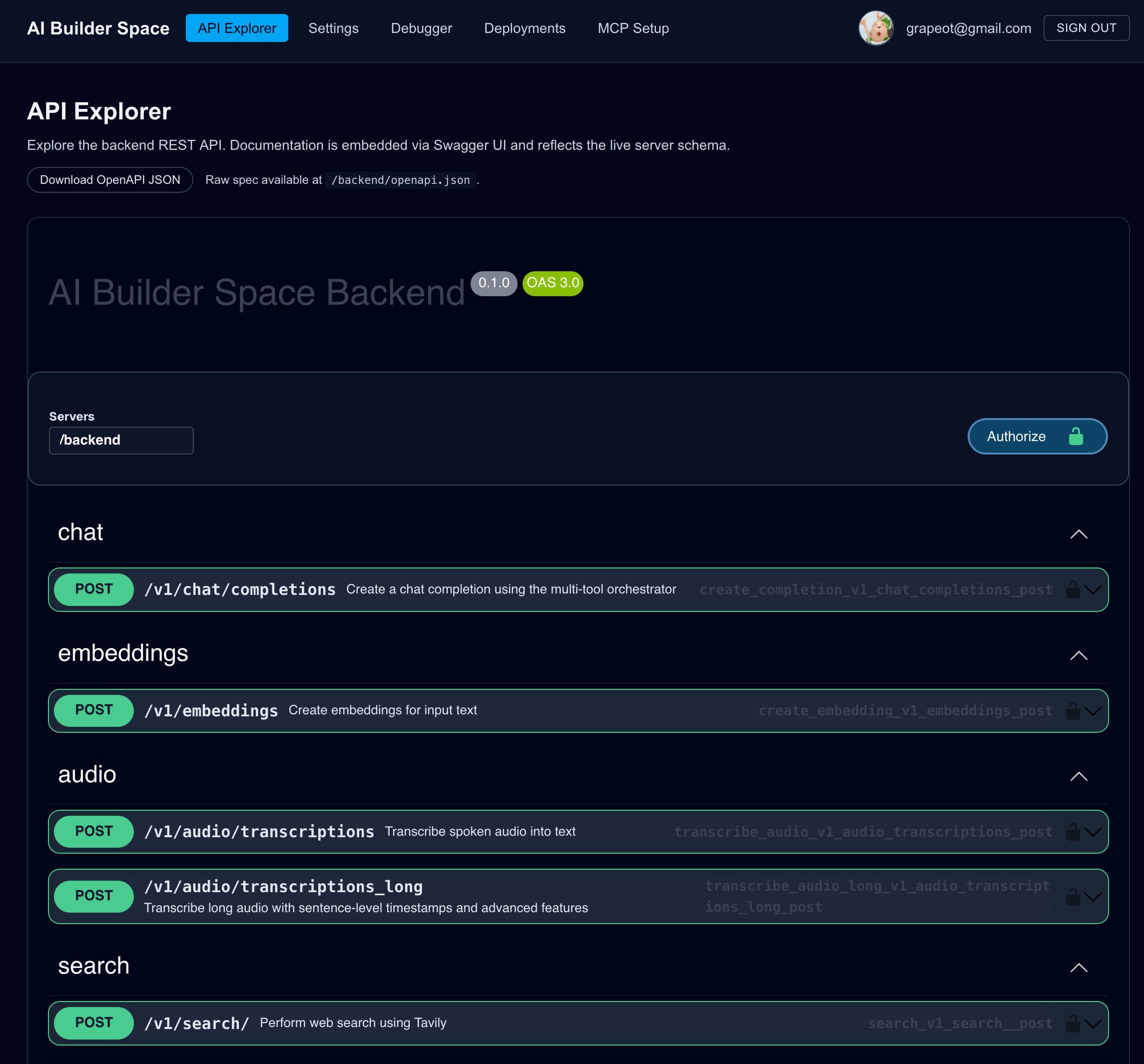

So our approach is: make these steps disappear. After registering for the course, students directly get a usable interface (API), with mainstream models like GPT, Claude, Gemini, DeepSeek, and Grok already connected behind it, plus capabilities like speech recognition, image understanding, image generation, and embedding. Since this platform is free for students, there's no need to bind credit cards.

On one hand, this makes calling various AI APIs particularly simple; on the other hand, it makes accumulating firsthand experience easy. Want to compare different models' performance? Just change one parameter. No re-registering, no re-configuring. The cost of experimentation is drastically reduced. We hope to use this method to encourage everyone to experiment more, try a few different models to see if there's improvement. Tired of typing? Try speech recognition. Want to add RAG, add web search? You can directly ask AI to add it. Our goal is to protect everyone's curiosity and drive to act with these easy-to-use APIs, helping them persist until the day they bear fruit.

Another thing we want to encourage is Build in Public—sharing what you've made so others can use it too.

The most obvious reason is the compound effect. On one hand, when you share your work, you start receiving feedback, start exchanging needs and ideas with others. This exchange helps polish your product thinking about what scenarios AI is useful for far more than exchanging how to call APIs. On the other hand, it's such a waste to finish something and then throw it away or just use it yourself. If you can put it on your resume, or if others actually use it, this value continues to accumulate.

Beyond this, there's something we only realized after interviewing students: many people feel a sense of loneliness while learning AI. On one hand, they fear being left behind by the times, feeling AI is important—which is why they took the course. But on the other hand, many people around them still don't understand what they're doing. Fighting alone to practice AI is a challenge to curiosity and drive. A month or two might pass, and because no one around is doing it, it gradually fades away.

So we really hope everyone can share what they build. This way, we can create a sustained immersion. You'll find you're not the only one doing this—many people share your passion for discussing these things. What our course wants to do isn't just teach you technology, but also lead you through the door to a community of like-minded people. The value of this community might be more lasting than teaching a few technical points. Also, if the AI tools you write can be used by people around you, it might change their attitudes and help them understand and support your AI learning.

So we did something: made deployment a very simple API. Write your code, (use one sentence to have Cursor) call the interface, and you have a real URL to share with friends. The domain is

The Last Piece of the Puzzle

The friction mentioned above—configuration, experimentation, deployment—were all things we anticipated from the start. But after AI Builder Space went live, we discovered there was one more problem we hadn't thought of.

Some students would ask: why can't I get your platform's API to work when I follow the documentation? At first we thought the documentation wasn't clear enough, but gradually we realized the problem was elsewhere: many people, when using AI coding assistants, don't provide enough context. They don't know to copy the API documentation or openapi.json to the AI, don't know doing so makes results much better. Without enough information, AI starts to hallucinate, and of course the results are wrong.

We could certainly write a tutorial teaching context curation. In fact, our materials already include this. But there's a more fundamental question: why, in the AI era, should we still have people copying OpenAPI docs around? This is an unknown unknown—people can hardly realize they need to do this. It's also a form of friction. We can't solve the problem by teaching everyone "you must do this high-friction thing well"—we should use the platform to eliminate this friction directly.

So we thought of an approach: could we solve this problem with something particularly easy to deploy? We chose MCP, mainly because it's so convenient to deploy—both Cursor and Claude Code support it, just run one command to install. After installation, students just need to say "use AI Builder Space to help me make an xxx," and the AI automatically knows how to call it and how to deploy. The platform's capabilities, best practices, and even API keys are all packaged inside. The results after launch were better than expected—both development and deployment experiences became much simpler.

When Tool-Level Problems Are Solved

Configuration problems solved, deployment problems solved, AI coding assistants can automatically understand the platform. But we found in our teaching that there's still one type of task that leaves many students stuck: research.

Many students' projects involve looking up information and summarizing. Seems simple, but if you've done extensive experiments you'll find: some models are diligent, running over a dozen search rounds when given a research task (like GPT, Kimi); other models are lazy about searching and just start making things up (like Gemini, even if you repeatedly emphasize searching first). This behavior is hard to change with prompts—it's more like a personality formed during model training.

If you try to build a research Agent from scratch yourself, just hitting these pitfalls, tuning these parameters, and designing workflows takes enormous amounts of time.

We spent a lot of effort on this problem, and our final conclusion was: don't expect one model to both search and think. So we made our own research Agent called Supermind Agent v1. It uses a Multi-Agent Handoff architecture—the research phase uses models good at tool calling (Grok, Kimi) to search, scrape, and filter; the thinking phase hands the organized materials to models good at deep reasoning (Gemini) for synthesis and expression.

Behind this design is a more general principle: use architecture to manage model uncertainty. The same model, same prompt, might perform differently today versus tomorrow; the same task, GPT and Gemini might have completely different behavior patterns. You can't change a model's personality, and there are limits to what prompts can adjust. But you can design an architecture that lets models good at certain things do those things.

This way of thinking is transferable. When you understand this principle, you can apply it to the design of any AI system. And when you use Supermind Agent to produce a high-quality research report and experience the effects of this combined use, you'll naturally want to understand the design behind it.

Conclusion: Waste Your Time on Beautiful Things

We've done all this infrastructure work—unified interfaces, one-click deployment, MCP automation—not to make AI easy. Quite the opposite: we did it so students can more quickly face the things that are truly difficult.

What are the truly difficult things? How to define a problem that's never been solved, how to design an elegant Agent architecture to handle ambiguity, how to catch that spark of logic in seemingly gibberish model feedback. These are the core competencies of the AI era, the work that only human brains can complete.

As for configuring environments, debugging ports, applying for tokens—these are false difficulties. They consume willpower, give people an illusion of working hard, yet don't grow your wisdom. We hope AI Builder Space is a sharp blade that cuts through these thorns entangling the learning path.

So don't learn for the sake of learning. Please cross those pointless technical barriers as quickly as possible and get to the place where you truly need to think, judge, and create. After all, life is finite—your curiosity and creativity should be wasted on things that are truly beautiful.

FAQ

Q: What is the AI Builder Space mentioned in the article? Where can I use it?

This is an exclusive educational platform for students of our AI Architect course. Its website is at space.ai-builders.com, but free access is limited to enrolled students.

If you are interested in this course, you can check out this link.

Q: There are already unified API gateways like OpenRouter, Portkey, and LiteLLM in the market. How is AI Builder Space different?

Functionally, there is indeed overlap. OpenRouter is currently the gateway with the most comprehensive multimodal capabilities, supporting LLM, Vision, Image Generation, Speech Recognition, Embedding, etc., and our unified API gateway is similar in this regard.

But the positioning is different. First, friction-free start—you automatically get an account and API key after registering for the course, without separate registration or binding a credit card, while OpenRouter requires you to register and bind a card yourself. Second, we provide an MCP Server to help AI coding assistants understand the platform, which other gateways don't have. Third, Unified API + One-click Deployment + MCP creates a complete loop from development to delivery, while OpenRouter only solves API calling, leaving deployment to you.

Simply put: OpenRouter is a great product, but AI Builder Space is a platform specifically designed for teaching.

Q: You helped me skip ahead, but I didn't learn the underlying things (like context curation, deployment principles). Is this okay?

This is exactly our intentional instructional design.

The traditional path is: Learn principles first → Do exercises → Finally do a project. Our path is: Build something first → Experience value → Come back to understand principles.

Why is the latter more effective?

First, the hardest part of education isn't knowledge transfer, but sparking learning motivation. Only when you've built a work you can share will you truly be motivated to understand how it works.

Second, before you understand the principles, you've already built intuition through practice. When you look back at the principles, you'll have many "aha" moments, rather than wondering "what's the use of this."

Third, learning too much at once can be overwhelming. Skip unnecessary complexity first, focus on the core, and fill in the gaps when you're ready.

Of course, this isn't to say those underlying knowledge points aren't important. The course will gradually guide you to understand the deeper logic of context curation, deployment principles, and prompt engineering later. But that's after you've already had a successful experience.

Q: You talk about cultivating Master Builders. How is this different from ordinary builders?

Low-level builders focus on specific details—how to call this API, how to set that parameter. Master Builders think from a product and system perspective: not how to use this model, but what system should be used to solve this problem; not how to write a good prompt, but how this task should be decomposed and orchestrated; not whether AI can do it, but how humans should fill the gap where AI falls short.

Supermind Agent is an example: when a single model has limitations, compensate with architecture. This shift in thinking is the most enduring competitiveness in the AI era.

We let you get started quickly by reducing friction, but the ultimate goal is to cultivate you into a Master Builder who can independently design AI systems. When you understand why it's designed this way, you no longer need to rely on any platform—including ours.

Comments