I've previously written about the history, flaws, and controversies of MCP. Half a year has passed, and MCP development is in full swing. Yesterday, OpenAI released its Apps SDK, which allows users to build GUI apps within ChatGPT using an extended version of MCP. This seems like another victory for the open protocol, following its adoption in ChatGPT Connectors and Google Gemini. However, after studying the details of the Apps SDK, I believe its release is a dangerous signal. It may not herald a renaissance for MCP, but rather, a crisis. This is a good opportunity to revisit the topic and share my further thoughts.

The Fragmentation of MCP Dialects

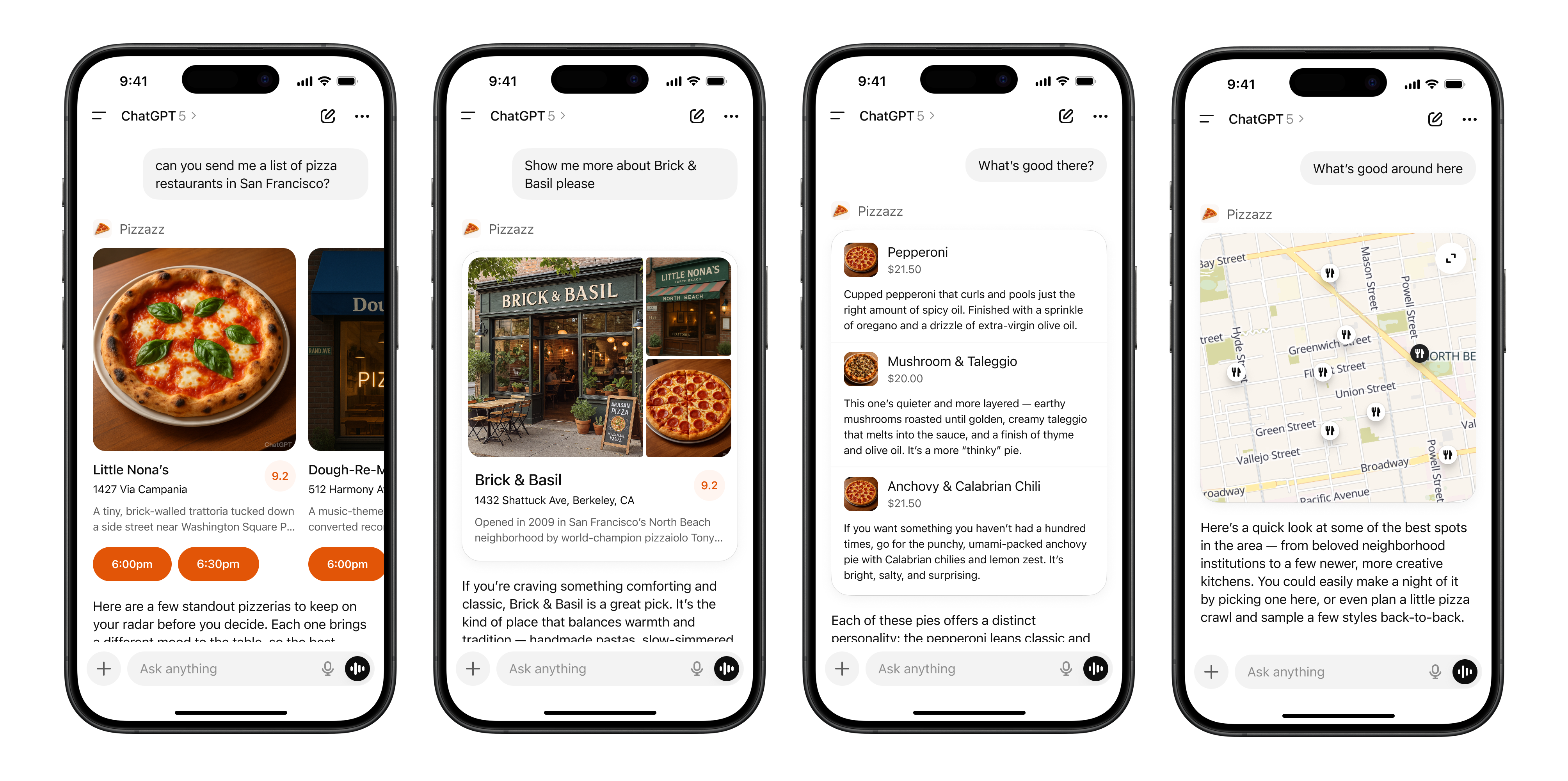

To understand the looming crisis, we first need to see how the Apps SDK utilizes MCP. ChatGPT already supported a feature called Connectors, where a developer deploys an MCP server, and OpenAI communicates with it exclusively using the MCP protocol. When a user enables a connector and GPT decides it can help answer the current query, it communicates with the developer's server via MCP. The Apps SDK builds on this by adding GUI capabilities, allowing the information returned by MCP to be not just interpreted by the LLM as plain text, but also rendered by OpenAI's GUI engine as a small card within the ChatGPT interface.

The design itself is fine. The problem lies in how it was implemented: the Apps SDK extends MCP by adding a _meta field outside the standard protocol:

_meta– Arbitrary JSON passed only to the component. Use it for data that should not influence the model’s reasoning, like the full set of locations that backs a dropdown. _meta is never shown to the model.

In OpenAI's documentation and examples, this field is used extensively, filled with complex structures and nested key-value pairs like openai/*. This allows developers to bypass the LLM's context window to pass various GUI-related information. It's a pragmatic and clever solution to MCP's limitations, meeting engineering needs. But it's also a dangerous sign: one of MCP's largest users is now inventing its own dialect of the protocol. This is similar to how various database vendors have their own dialects on top of standard SQL—MSSQL, Databricks, etc.—that are incompatible with each other, making the standard exist in name only. What's more dangerous is that while SQL dialects add nice-to-have features that can be incorporated into the standard, what ChatGPT is doing fundamentally violates MCP's design philosophy.

An Elegant Protocol Born in an Ivory Tower

MCP was designed by top AI scientists at Anthropic. Its original purpose was to allow researchers to rapidly iterate on Agentic AI in a lab setting. Therefore, its design revolves around a central question: What could AI become if LLMs could call many different tools? What unexpected benefits could it bring to humanity, and what are its limits? This is an ambitious and impactful research area. And because it's a protocol for research, not engineering, MCP was born with many elegant design principles. For example, the LLM should be at the core of all decisions, with full visibility and control over all tool calls and their results. In other words, all information exchange must pass through the LLM's context window.

This design philosophy is perfectly reasonable. On one hand, it effectively supports the core mission of exploring the boundaries of LLM capabilities. If an LLM doesn't know the result of its own tool call, it's irrelevant to LLM capability research. On the other hand, it cleverly decouples the thorny engineering problem of state management from the protocol itself. State is managed entirely by the LLM through its context window, making the protocol stateless.

But as we'll see, this beautiful design, while effective in the lab for exploring Agentic AI applications, is ill-suited for the real world of engineering. For instance, if I want to build a flight search app, the MCP flow would look like this:

- User: "Find me a flight from Seattle to San Francisco tomorrow."

- LLM: Understands user intent and calls the flight search tool via MCP.

- MCP: Performs the search and returns a JSON object.

- LLM: Reads the result and describes it to the user: "There are three flights, at these times..."

This works fine when the LLM communicates with the user in natural language. But when we want to introduce a GUI—for example, rendering an HTML view for the user in step 4—the "all information must pass through the context window" design immediately becomes a major bottleneck.

First, whether the HTML is generated by MCP or the LLM, it will be bloated and have low information density, polluting the context window. This degrades the LLM's intelligence and increases inference costs.

Second, ensuring that an output of tens of kilobytes is free of syntax or minor errors is still a challenge for current LLMs. Even when simply relaying programmatically generated HTML, an LLM might get lazy or misplace a character. This might be fine for natural language, but for deterministic tasks like UI rendering, it leads to failure.

Third, the user doesn't even need the LLM's intelligence in this part of the process. Rendering a JSON object into HTML is a deterministic task that can be perfectly handled by a traditional program.

So, for tasks like GUI rendering that traditional programs can solve, forcing all information through the LLM's context window introduces uncertainty, reduces task success rates, degrades LLM intelligence, and increases costs. It's all harm and no benefit. This is why OpenAI poked a hole in MCP with the _meta field, to pass engineering state invisible to the LLM and bypass the context window.

The root of the issue is that MCP was born for Agentic AI research. Problems solvable by traditional computer programs were never in the researchers' interest, so MCP naturally didn't need to support them. The problem is that MCP received too much attention from investors and the engineering world from its inception. Swept up by media and public opinion, developers started using MCP for applications it was never designed for. This forced an immature protocol to carry burdens beyond its design goals, causing pain for the entire field.

A Stumbling Development

In fact, this isn't the first time we've seen such struggles. There has been ongoing debate about MCP's suitability for real-world engineering. Three examples are perhaps the most well-known:

First, its early use of stdio for interaction. From an engineering perspective, this was an amateurish choice that completely ruled out remote servers. It was finally corrected by the community a year or two later.

Second, it was designed without any consideration for authentication and authorization. This was reasonable in a research context but created massive chaos in subsequent engineering applications. Everyone implemented their own auth methods, leading to MCP fragmentation. Then, an official attempt to fix this with OAuth 2.1 both exposed too many implementation details, creating a poor developer experience, and introduced numerous security vulnerabilities. After much drama, another breaking change was introduced, which, while solving (or rather, shifting) most of the problems, imposed additional migration costs on companies already using MCP.

Third, being based on JSON-RPC, it has no type checking. All errors are exposed only at runtime. It also lacks standard distributed systems designs for observability and debuggability, like tracing and IDs, making debugging excruciating.

In short, its design philosophy is beautiful and elegant, but it is retracing decades of hard-won lessons in RPC engineering and is, at present, far from mature from an engineering standpoint.

Of course, a standard is not purely a technical issue; the best technology doesn't always win. But MCP's foundational design lacks engineering considerations, and its early, massive media attention attracted significant investment. This prevents anyone from starting over, forcing them, like OpenAI, to poke holes in the standard and invent new dialects. This is reminiscent of the browser wars and SQL language wars, where vendors lock in customers with their proprietary implementations, forcing the standard to evolve in response.

This is also a form of power play between OpenAI and Anthropic. By introducing the private _meta field, OpenAI now has the power to define its own (variant of) MCP. Adding openai/* protocols within this field, from a political perspective, gives OpenAI the power to define AI capabilities and formats, to some extent undermining Anthropic's control over MCP. For example, once a developer deeply integrates the openai/* _meta structure, their application is no longer a generic MCP application but a tightly-coupled ChatGPT App. The app transforms from an implementation of an open standard into a part of OpenAI's corporate moat.

The Future Is Hidden in the History of Other Open Standards

The next natural question is: what is the future of MCP? I would say that there is nothing new under the sun. We can perhaps look at four examples of open standards.

The first is the HTTP protocol. It is an open, standard protocol with virtually no dialects. People build applications on top of it, but you don't hear someone say, "My protocol is compatible with HTTP but adds some extra features."

The second is the USB interface. It has many variations, like 2.0, 3.0, etc., but apart from Thunderbolt, it's rare for a manufacturer to say, "I made a USB-compatible port that adds some functionality."

The third is the SQL language. The language itself is standard, but providers like Databricks, MS SQL Server, and others have their own dialects. They are compatible with traditional SQL but add their own proprietary features, making them incompatible with each other. For example, specialized SQL written for Databricks won't run on MS SQL.

The fourth is CSS. CSS is a standard, but browsers like Webkit, Mozilla, etc., have their own specializations, forming their own dialects. A CSS that renders correctly in a Webkit browser may not render correctly in another ecosystem, like Firefox.

These four examples share a common trait: they are all seemingly standard, universally supported technical interfaces. But they can be divided into two categories. One is the "pipe" type, which is plug-and-play. A USB device from manufacturer A will almost certainly work with a motherboard from manufacturer B. A Windows HTTP stack can accept requests from a Linux client, and Nginx can parse and manipulate headers from Apache, all with 100% success. The other category, also open standards, is more focused on expressiveness and has thus fragmented into various versions. Databricks SQL won't run on MySQL, and Mozilla-specific CSS won't render correctly in Chrome.

I am pessimistic and believe MCP is more like the latter. On one hand, it's an expressive, content-related protocol. Today it needs to support GUIs, tomorrow live video streaming—it has a natural tendency to fragment. On the other hand, its premature explosion in popularity forced it to take on engineering responsibilities before it could shed its academic skin. Over the past year, we've seen the entire Agentic AI field struggle to advance under MCP's idealized, research-oriented design. And now, we see a major vendor violating its most basic design principles to smuggle in their own features via a private dialect. The fragmentation of the standard has become a hidden reality.

So, OpenAI's new SDK, while appearing to be a victory for MCP, actually harbors a deeper crisis. I have a few predictions for the future. One possibility is that OpenAI effectively hijacks MCP, much like IE6 became the de facto standard for CSS. Another is that, similar to how SQL dialects drove everyone crazy and led to higher-level abstractions like JDBC/ODBC, we might see an "MCP of MCPs" emerge—a unified semantic protocol that translates into OpenAI's Apps MCP, Anthropic's purist MCP, Google's A2A, and so on. The outcome will depend on the technical and political battles among these players.

Comments